Edinburgh Buddhist Studies proudly presents an insightful glimpse into the Buddhist objects displayed at the National Museum of Scotland. Delve deeper into the history, significance, and stories behind each exhibit. Our comprehensive descriptions provide visitors with a richer understanding of the artefacts and their place within Buddhist culture. Join us for an educational journey and connect with the profound legacy of Buddhist teachings through these tangible pieces of history.

More stories and visuals are coming soon – keep watching this space!

Central to Buddhist practice is the idea that to be in the presence of a Buddha has great spiritual benefit. A Buddha is primarily a great teacher, and, like many great teachers, he can aid in his audiences understanding. Just to be there, in his presence, can accomplish a leap, a resounding breakthrough in the overcoming of suffering.

One can imagine that in the actual vicinity of the Buddha, in 5th century BCE India, that he had a field of influence. We all have a field of influence, but the idea seems to be that certain individuals have an influence which is profound. For example, imaging being in the presence of someone extremely famous, a singer or musician. The concert venue is filled with the aura, the passion, the magnetism of the performer. It can be mesmerising, uplifting, and in some senses, a transformative experience. It seems that the Buddhists understood a Buddha along similar lines, but in a greatly enhanced and amplified way. If you want to achieve awakening, then the good fortune to be born at the time of a Buddha is profound.

After the historical Buddha, from around the beginning of the common era, a new pantheon of Buddhas began to appear. With the Buddha a distant memory, a spiritual yearning, or a religious outlet was opened. One could hope to be reborn at the time of the next Buddha, Maitreya, or, one could aspire to be reborn in the presence of other Buddhas.

In a new body of texts, the spiritual accomplishments of these Buddhas are described. In a sense, the historical Buddha becomes less important. These Buddhas are newer, better, more profound, and their spiritual accomplishments can be of great benefit to their followers. In a sense, they are embodiments of religious conversion as Buddhism spread East into China and Japan.

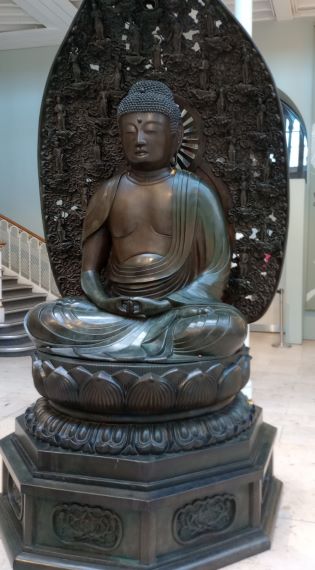

This statue is that of Amida Buddha. He is also known as Amitābha, the Buddha of infinite light and Amitāyas, the Buddha of infinite life. Amitābha’s spiritual accomplishments are so great that he has created a special place, a field of influence like that of the historical Buddha, where his followers can be reborn in his presence.

This Pure Land is known as Sukhāvatī, a place devoid of suffering, in fact it is filled with a subtle type of happiness. It is a place where everyone is Buddha-like. They are golden and devoted to the practice of Buddhism. The devotee aspires to be reborn in that Pure Land, and from there they achieve awakening. It is not a heaven of pleasure, but a Dharmic or spiritual place of truth, where the teachings of Amitābha bristles through the trees, and one’s awakening is assured.

How is this possible? It is because of a vow that was made by Amitābha an unimaginable long time ago.

May I not gain possession of perfect awakening if, once I have attained buddhahood, any among the throng of living beings in the ten regions of the universe should single-mindedly desire to be reborn in my land with joy, with confidence, and gladness, and if they should bring to mind this aspiration for even ten moments of thought and yet not gain rebirth there. This excludes only those who have committed the five heinous sins and those who have reviled the True Dharma.

This vow became true because Amitābha did achieve awakening. There’s a lot happening in this statement, suggesting that those who have acted in a particularly unethical way, such as wounding a Buddha, or killing one’s parents are excluded from his Pure Land. However, there is a focus upon aspiration, a quality needed to reach the pinnacle of the Buddhist path. There is also the idea mentioned above of being close to a Buddha, and that being in his presence will expediate a person’s awakening.

It is therefore fascinating to view the Buddha in the museum, reflecting on what he means, the aspirations and promises he fulfils to the Buddhist who wants to go, at their own passing, to his Pure Land of Sukhāvatī.

(Content and photography by Paul Fuller)

This is a Chinese Buddha from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) from the 16th Century. In s similar way that nations and political parties, cultures and tribes, clans and sports teams use statues as collective reminders of their identities, so does Buddhism. Statues of the Buddha are one of the most common features of Buddhism in Asia.

While evoking a collective memory, they also express the presence of a Buddha. To visit a Buddhist temple, or to have a Buddhist shrine on one’s home brings the devotee closer to the Buddha. In Buddhist writings is suggested that the presence of the Buddha can expedite the overcoming of suffering. Being in the presence of a Buddha, or his image or statue can get one closer to liberation.

The life of the Buddha is one of the most familiar stories in human history. It is often summarized according to twelve episodes, or acts, that all Buddhas follow.

First, a Buddha dwells in the Tuṣita heaven. Buddhists understand an endless cycle of existences for all individuals, including Buddhas. The Tuṣita heaven is a place where individuals can be reborn. It holds a special place in Buddhism as it is the abode of Buddhas who are about to take their final existence on earth.

Second, a Buddha makes his descent from the Tuṣita heaven, and thirdly they enter their mother’s womb. The fourth act of a Buddha is to be born. As we might expect, many stories are told about his birth. It is embellished by the newborn Buddha-to-be making a momentous announcement:

I am the highest in the world; I am the best in the world; I am foremost in this world. This is my last birth, now there is no renewal of being for me.

The fifth act of a Buddha is to become skilled in various worldly arts. The Buddhist tradition portrays him as the perfect being, even before he accomplishes perfection on the religious path. The sixth act of a Buddha suggests how he lives a life of luxury. The seventh act describes how he becomes disillusioned with sensual desire and makes his departure from the palace. It is often said that this was after seeing old-age, sickness, and death. Having seen a wandering holy person, known as an ascetic, who has gone from the home to the homeless life, the eight act of a Buddha is to undertake a period of extreme religious practice. It is during the final part of this period, often said to last six years, that he defeats the embodiment of greed, hatred, and delusion, in the form of an intriguing figure called Māra, a tempter figure in Buddhist mythology. The defeat of Māra is the ninth act of a Buddha.

The tenth act of a Buddha is when, after the longest and most arduous path. attains awakening, and becomes awakened, a Buddha. He goes on to give his first sermon, the eleventh act of a Buddha. It is stated at this time that he taught four truths about human existence and the Buddhist path; that there is suffering, that its cause is craving, that liberation can be attained, and that the Buddhist path accomplishes this.

The twelfth act of a Buddha is his final awakening achieved when he passes away. Shortly before this, it is said that he uttered his final words:

All conditioned things are subject to decay. Attain perfection through diligence.

In travelling around Asia, as is the case with this Buddha from China, his image conveys to devotees a memory of these acts, performed in his final birth. Importantly, this is not simply considered an image, but an embodiment of the qualities of the Buddha. It is, therefore, well worth visiting the museum to stand before the Buddha and to experience the ideas his statue might evoke. He is imbued with ideas, accomplishments, and teachings about what it means to exist.

(Content and photography by Paul Fuller)

This article was published on